OTTI THE “EVIL GENIUS”: HOW DISRUPTIVE REFORMERS ARE MISREAD IN REAL TIME

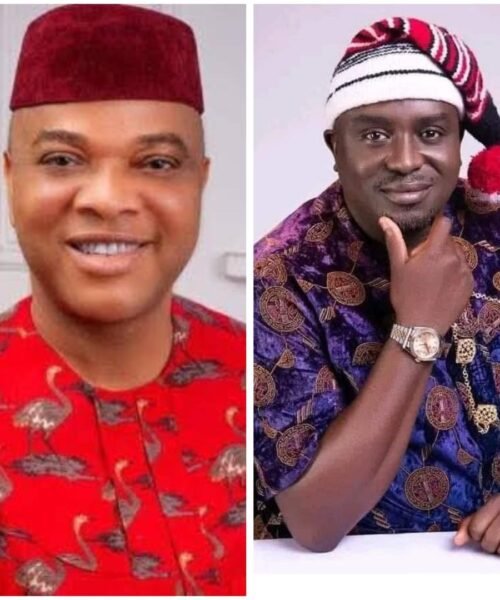

In political discourse, labels often travel faster than facts. Few phrases illustrate this better than the loose and increasingly careless use of the term “evil genius” in describing Governor Alex Otti of Abia State. The phrase, borrowed from Nigeria’s long history of elite political commentary and pop culture, has been deployed online not as a serious analytical category but as a shorthand for discomfort with disruption.

Historically, the term “evil genius” entered Nigeria’s political lexicon through debates around Ibrahim Babangida, whose strategic brilliance was often acknowledged even by his fiercest critics. In that context, the phrase carried moral weight because it was attached to authoritarian power exercised without democratic accountability. To recycle that language today—within a constitutional democracy and against an elected governor operating under legislative, judicial, and media scrutiny—is analytically lazy and intellectually dishonest.

What is happening in Abia is not the rise of an “evil genius” but the emergence of a reformer whose methods have unsettled entrenched interests.

Governor Otti’s administration has been marked by a deliberate departure from Abia’s historical governance style. From aggressive asset recovery to fiscal tightening and the dismantling of long-standing patronage pipelines, the government has chosen disruption over appeasement. This is not a personality trait; it is a policy orientation. And as political economy literature has long shown, reformist governments attract resistance precisely because they alter who benefits from the system.

The backlash against Otti has therefore followed a familiar pattern. Critics focus less on outcomes and more on tone, branding decisiveness as arrogance and firmness as cruelty. Social media commentary amplifies this framing, often collapsing complex governance decisions into moral drama. Yet when stripped of rhetoric, the record shows a government pursuing measurable institutional change.

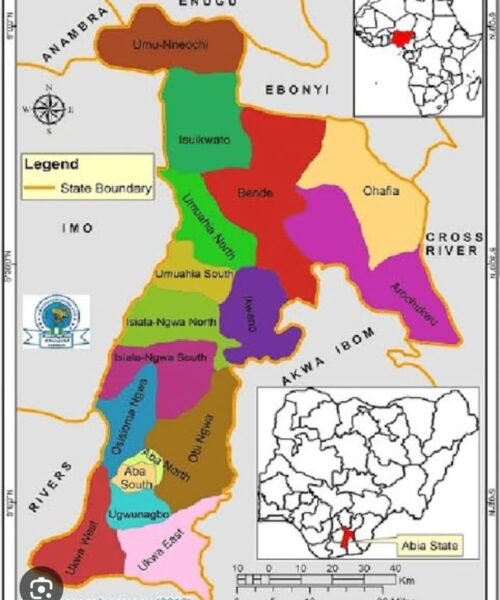

Abia’s internally generated revenue has risen significantly since 2023, according to state finance disclosures and independent budget trackers. Urban infrastructure renewal in Aba and Umuahia—roads, drainage, traffic systems—has moved from episodic patchwork to coordinated planning. The recovery of moribund public assets, including industrial facilities previously lost to opaque transactions, reflects a governance philosophy anchored in restitution rather than recycling failure.

Even in sectors where outcomes are still unfolding—industrialisation, education reform, healthcare systems strengthening—the approach is structurally different from the past. Projects are sequenced, contracts are being reviewed, and legacy liabilities audited. These processes are slow, visible only to those who understand governance beyond ribbon-cutting, but they are foundational to sustainable development.

The “evil genius” label also collapses under comparative scrutiny. In pop culture, the phrase has been stripped of moral content entirely, used ironically or aesthetically—as in **Mr. Eazi’s album The Evil Genius—to signify boldness, independence, and creative control. Ironically, that cultural meaning is closer to what critics unintentionally describe in Otti: a leader unwilling to be captured by expectations of transactional politics.

What truly fuels the hostility, however, is not fear of genius but fear of precedent. If Abia demonstrates that a subnational government can recover assets, publish fiscal data, challenge inherited rot, and still retain political legitimacy, then excuses elsewhere begin to collapse. That is the deeper anxiety playing out online.

None of this suggests that Governor Otti is beyond criticism. Democratic accountability demands scrutiny of procurement decisions, project execution, and policy trade-offs. But criticism anchored in evidence is fundamentally different from narrative warfare built on caricature. Calling a reformer an “evil genius” is not analysis; it is resistance dressed up as wit.

In the end, political reputations are not settled on timelines or hashtags. They are settled over time, through institutions strengthened or weakened, through cities that function or decay, through whether public wealth is preserved or plundered. By that standard, Alex Otti’s story is still being written—but it is already clear that disruption, not malevolence, explains both his methods and the fury they provoke.

History rarely remembers the noise. It remembers outcomes.

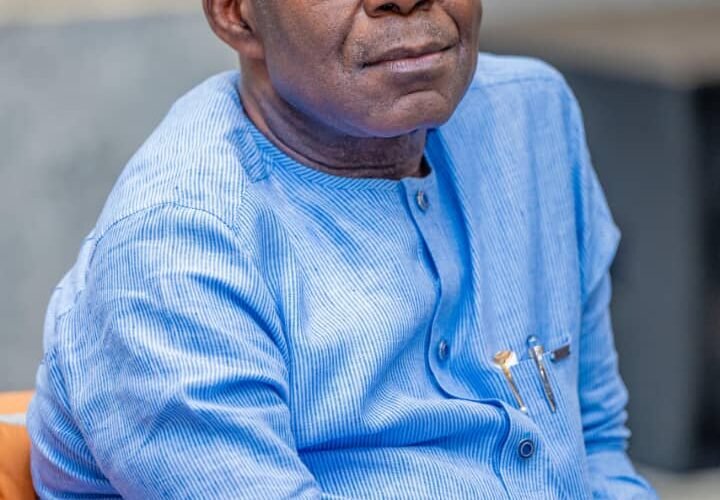

AProf Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke