FROM MORIBUND ASSETS TO LIVING INDUSTRIES: HOW ABIA’S DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY FITS GLOBAL GOVERNANCE THEORY

Reclaiming Failed Assets and the Logic of Developmental States

When the Asset Management Corporation of Nigeria (AMCON) formally handed over Star Paper Mill to the Abia State Government in December 2025, the moment represented more than the recovery of a long-abandoned industrial facility. It illustrated what Robert H. Bates describes in The Politics of Development as the defining test of governance in post-colonial states: the ability of political leadership to reverse institutional decay rather than merely manage decline. Bates argues that development occurs when governments confront the political incentives that allow productive assets to collapse, noting that “states fail when rulers find it easier to extract than to rebuild” (Bates, 1981).

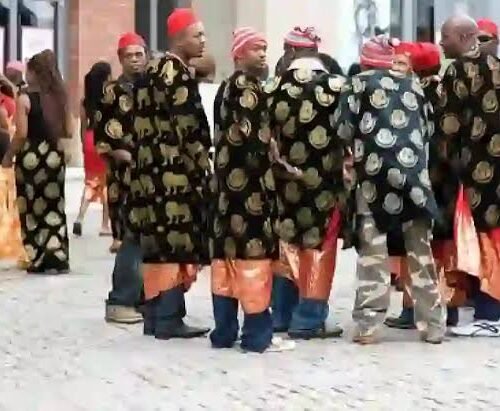

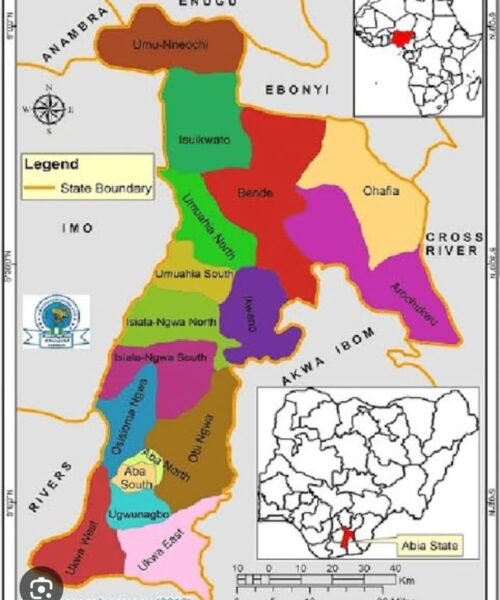

Star Paper Mill, founded in 1976 by the late Chief Nnanna Kalu, once provided thousands of jobs and anchored Aba’s industrial ecosystem. Its collapse mirrored the broader Nigerian industrial tragedy of the 1980s and 1990s, when poor governance, debt crises, and asset stripping hollowed out productive capacity. AMCON Executive Director Aminu Mukhtar Dan’amu captured this historical weight when he described the mill as “an icon woven into the history of Abia State and Nigeria,” adding that its revival could generate between 3,000 and 5,000 direct and indirect jobs. In governance terms, this aligns with Bates’ observation that employment is not merely economic output but a political stabiliser that restores trust between citizens and the state.

Why Government De-Risking Matters More Than Government Ownership

Governor Alex Otti’s insistence that the Abia State Government does not intend to run Star Paper Mill but to “de-risk it and hand it over to capable private investors” places the policy squarely within modern development economics. In Why Nations Fail, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson argue that sustainable growth emerges when governments create inclusive economic institutions that protect property rights, enforce contracts, and reduce uncertainty, rather than when they attempt to replace markets outright. “The state must be strong enough to enforce rules,” they write, “but restrained enough not to suffocate private initiative” (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012).

By intervening to recover the asset from questionable prior transactions, refund disputed payments, and restore legal clarity, the Abia government acted as an institutional repair mechanism. This approach echoes the World Bank’s thesis in Making Services Work for Poor People, which stresses that the most effective governments focus on lowering risks for investors and citizens alike, rather than becoming perpetual operators of enterprises. In this sense, the Star Paper Mill handover reflects governance through rule-setting, not command-and-control.

Industrial Revival and the Political Economy of Jobs

The promise that Star Paper Mill could once again employ thousands resonates with what Ha-Joon Chang describes in Kicking Away the Ladder as the historical pathway of successful industrialisers. Chang shows that countries that industrialised did so through deliberate state action that rebuilt domestic productive capacity before exposing industries fully to market competition. Abia’s strategy—recover, stabilise, then invite private operators—fits this sequencing. It avoids the twin pitfalls of laissez-faire abandonment and inefficient state ownership.

The involvement of business associations such as ACCIMA and UCCIMA further reflects this logic. In Governing the Market, Wade argues that effective development states embed policy within networks of domestic producers, creating feedback loops between government and industry rather than governing in isolation. Governor Otti’s challenge to chambers of commerce to take leadership in operationalising revived industries signals an attempt to rebuild those networks.

Healthcare Investment and Human Development as State Capacity

Abia’s emergence as the top-ranked South East state in the 2025 Nigeria Governors’ Forum Primary Healthcare Leadership Challenge reinforces the same governance philosophy applied in a different sector. The NGF’s Performance Monitoring Framework evaluates governance, financing, quality of care, evidence, and sustainability—criteria that mirror the human development metrics outlined by Amartya Sen in Development as Freedom. Sen famously argued that development should be measured not by income alone but by the expansion of people’s capabilities to live healthy, productive lives.

Governor Otti’s remark at the awards ceremony—“We don’t look at healthcare spending as an investment… we see it as a necessary condition for people to survive”—could have been lifted directly from Sen’s thesis. Sen warned that treating health purely as an economic investment risks neglecting its intrinsic value as a foundation of human freedom. Abia’s consistent allocation of roughly 15% of its budget to health aligns with this perspective and explains why the state topped the 2025 SBM Health Preparedness Index with a score of 26.85, as reported by SBM Intelligence.

Transparency, Credibility, and the Politics of Trust

Underlying both industrial revival and healthcare performance is the question of credibility. In The Logic of Political Survival, Bueno de Mesquita and colleagues argue that leaders who rely on broad public support rather than narrow patronage networks are incentivised to invest in public goods such as infrastructure, health, and jobs. Abia’s publication of budget performance reports and its measurable improvement in fiscal transparency reflect this shift toward what BudgIT and other civic monitors classify as open governance practices.

This is why narratives alleging systemic opacity or internal collapse struggle to withstand scrutiny. As BusinessDay observed in a 2025 analysis of subnational reform, states that consistently publish fiscal data and deliver verifiable projects “reduce the space for disinformation precisely because the records are open.” Transparency, in this sense, is not just administrative virtue but political defence.

Federal–State Collaboration and Institutional Repair

AMCON’s cooperation with Abia illustrates what Douglass North described in Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance as the importance of institutional complementarity. Development accelerates when national and subnational institutions align rather than work at cross-purposes. Dan’amu’s statement that the handover underscores “the importance of Federal-State collaboration in preserving strategic national assets” reflects this principle and counters the notion that subnational reform can succeed without federal engagement.

Conclusion: Governance Beyond Slogans

Seen through the lens of global development literature—from Bates and Sen to Acemoglu, Chang, and North—Abia’s recent actions form a coherent pattern rather than isolated events. The recovery of moribund industries, the emphasis on de-risking rather than state control, sustained healthcare investment, and measurable transparency all point to a governance strategy grounded in institutional rebuilding.

As Robert Bates concluded decades ago, “development is not a mystery; it is the outcome of political choices that reward production over predation.” In Abia today, those choices are visible in policy, data, and outcomes—not merely in rhetoric.

AProf Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke