From Tax Reform to Power Stability: Why Otti’s Fiscal and Energy Agenda Signals a Structural Shift in Abia’s Governance Model

By Prof. Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke

In public sector reform history, the most consequential transformations rarely begin with ribbon cuttings. They begin with systems — how revenue is raised, how power is supplied, and how predictability is restored to economic life. That is the deeper significance of Governor Alex Otti’s visible alignment with national tax reforms and his administration’s push toward energy independence for Abia State. Taken together, these are not isolated policy positions. They represent a structural governance direction: stabilize revenue, stabilize power, and build growth on institutional foundations rather than fiscal improvisation.

Across reforming jurisdictions worldwide, tax reform has always been politically difficult but economically necessary. Governments that modernize their tax systems — through digitization, compliance automation, and base-broadening — typicbally move away from opaque, personality-driven revenue collection toward rule-based fiscal architecture. Otti’s defense of contemporary tax reforms is grounded in this logic. His argument, consistently, is that critics often see tax reform as punishment, while reform economists see it as capacity — the capacity of the state to fund services without reckless borrowing or hidden liabilities. When tax systems become more transparent and technology-driven, leakages reduce, planning improves, and budget credibility strengthens.

This is not theory alone. Development finance literature and comparative governance records show that subnational governments that build predictable internally generated revenue systems gain three advantages: better creditworthiness, stronger medium-term planning, and reduced dependence on volatile transfers. In practical terms, this allows a state to plan infrastructure, health, and education spending with greater certainty. Otti’s pro-reform posture on taxation signals an intention to move Abia from discretionary revenue culture to auditable revenue structure — where collections can be tracked, forecast, and tied to measurable service outcomes.

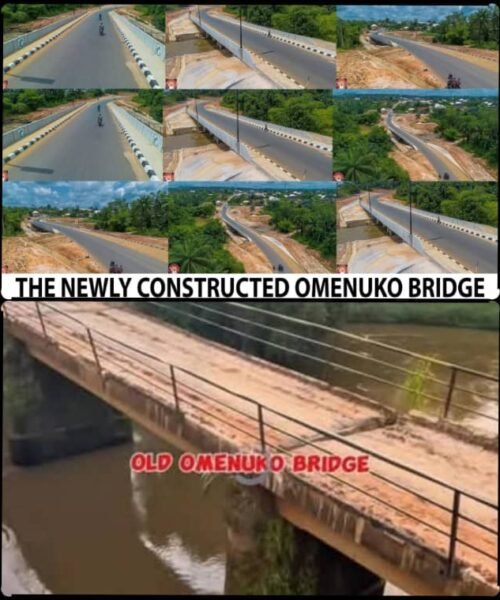

Running parallel to fiscal reform is the administration’s energy strategy — arguably even more economically decisive. Frequent national grid collapses have historically imposed hidden taxes on Nigerian businesses: diesel costs, generator maintenance, downtime losses, and equipment damage. By pursuing embedded and independent power solutions and positioning Abia as increasingly insulated from national grid instability, the Otti policy direction treats electricity as productivity infrastructure, not political decoration. Stable power supply reduces operating costs, extends business hours, improves hospital reliability, supports digital governance systems, and attracts manufacturing and processing investments.

Economic history is unambiguous on this point. Regions that achieve early gains in power reliability tend to outperform peers in SME survival rates and industrial clustering. Energy stability is one of the quiet multipliers of growth. It does not trend on social media as easily as road commissioning ceremonies, but it compounds value daily across thousands of enterprises. The Abia energy push — including independent and hybrid supply models — fits squarely within this reform tradition: build resilience first, optics later.

There is also a governance philosophy embedded in these twin reforms. Tax modernization without power stability frustrates taxpayers. Power reform without fiscal reform starves the grid of funding. When both are pursued together, a reinforcing loop emerges: better revenue funds better infrastructure; better infrastructure expands the tax base. That circular logic is the backbone of durable state-level development models from Asia to parts of Latin America and Eastern Europe. It is a systems view of governance — one that prioritizes institutional plumbing over performative politics.

Criticism, of course, remains legitimate in any democracy. Reform policies must be scrutinized, numbers must be questioned, and outcomes must be verified. But serious evaluation should follow standards: revenue reports, budget performance documents, procurement disclosures, sector metrics, and service delivery data. Tax and power reforms are not judged by volume of applause or outrage, but by compliance rates, outage reductions, cost savings, and productivity gains over time.

What further actions logically flow from this reform direction? First, full revenue digitization — unified taxpayer databases, automated assessments, and reduced human discretion in collections. Second, performance-linked budgeting — where spending proposals are tied to measurable outputs. Third, expansion of embedded power for industrial and commercial clusters. Fourth, deeper integration of energy planning with SME and agro-processing zones. Fifth, public dashboards that connect revenue inflows to sector expenditures for citizen verification.

In reform governance, intentions matter — but systems matter more. A state that fixes how it earns and how it powers its economy is not merely governing for the present budget cycle; it is engineering future capacity. That is the broader story behind Abia’s tax reform alignment and energy independence drive: a shift from episodic governance to structural governance.

History suggests that when revenue rules and power stability improve together, development stops being accidental and starts becoming repeatable. That is the reform wager now being placed — and it is one that will ultimately be judged not by slogans, but by records.