*WHEN A COURT LOSES ITS TEXT:

How Citizens Must Critique a Questionable Judgment in a Constitutional Democracy*

AProf. Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke

University of Abuja

A New Frontier: Critiquing the Judiciary, Not the Government

A number of respected readers raised profound concerns after my earlier essay on critiquing government. Their central question was simple but weighty: How do we critique a court that is constitutionally assumed to be competent? This question deserves its own full treatment, not as an appendix to the earlier essay but as a necessary continuation of it.

Critiquing the judiciary is not sedition; it is a constitutional duty. The Nigerian Constitution places sovereignty not in judges, not in politicians, not in institutions, but in the people themselves under Section 14(2)(a). The judiciary acts on delegated power, not divine authority. Therefore, when a trial—especially one as consequential as that of Mazi Nnamdi Kanu—appears to proceed without the anchor of written law, the people are obligated to interrogate it.

The People’s Concern: “Show Us the Law”

Multiple contributors highlighted the same problem: the judgment allegedly failed to reference any written law. This is not a minor procedural slip; it is the constitutional oxygen of every criminal conviction. Section 36(12) of the 1999 Constitution is emphatic:

“A person shall not be convicted of a criminal offence unless that offence is defined and the penalty prescribed in a written law.”

If no such law was read out, cited, referenced, or tendered, then citizens have every right—not merely the right, but the obligation—to demand clarity, because the Constitution demands it on their behalf. The Constitution does not require obedience to a judge; it requires obedience to the law.

A court becomes questionable not when citizens doubt it, but when it refuses to show its legal foundation.

International Mirror: When Foreign Decisions Reflect Local Failings

One reader raised the example of Finland and the United Kingdom and asked whether their decisions had a proper legal basis. They did. The Finnish government, for instance, acted based on national security statutes specific to their jurisdiction. The British government acted based on immigration and security protocols also rooted in their domestic law.

This comparison actually strengthens the point: those decisions were grounded in written laws. If Nigeria wishes to be respected in the international legal community, it must apply the same standard of written, cited, accessible law. It is therefore irrelevant that foreign governments took decisions on Kanu; what matters is that each did so under identifiable domestic statutes. A Nigerian court cannot act on emotions, politics, “knowledge”, or assumptions—it must act on a written law.

The Legal Core of the Debate

The readers expressed worry that a court of competent jurisdiction could deliver a life sentence without citing a textual basis. This is the exact moment when civic criticism becomes indispensable. The judiciary is competent only to the extent that it is textual. The moment a judgment departs from the text, it departs from constitutional legitimacy.

Justice must explain itself.

Justice must reference its authority.

Justice must show its working.

A judgment without a law is a decree.

A decree in democracy is unconstitutional.

And an unconstitutional judgment must be critiqued.

Extraordinary Rendition and the Illegality of Process

Another reader asked: What about the Kenya ruling? What about ECOWAS? What about the process? These questions matter because both domestic and international courts have already established that Kanu’s extraordinary rendition was unlawful. The Kenyan High Court (2022) awarded damages for the illegal abduction.

The ECOWAS Court (2018) ruled that Nigeria violated his fundamental rights.

The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention flagged concerns.

The criminal process, therefore, was already contaminated before it reached the courtroom. You cannot build a constitutional house on an unconstitutional foundation. Process is everything in law; the wrong process cannot produce the right outcome.

Readers’ Concern: “Shouldn’t elders intervene?”

Another contributor insisted that southeastern elders should intervene so the debate does not escalate into online warfare. Intervention is noble, but it does not replace legality. Dialogues soften tensions; they do not correct unlawful judgments. Mercy may be political; justice must be legal.

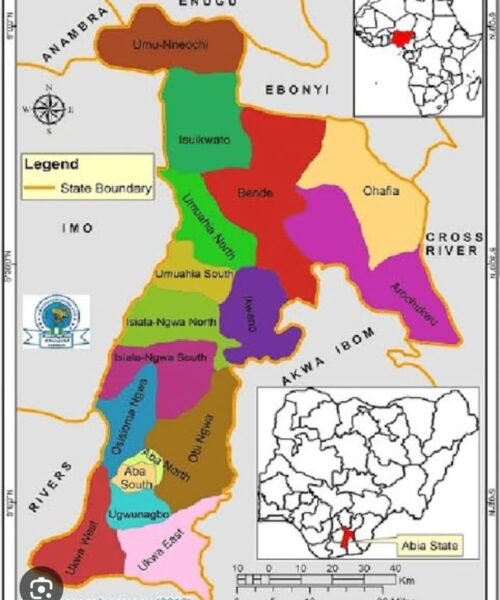

This is why many, including the concerned reader from Nchara in Ohafia, insist on transparency: the people need to know the legal foundation of the conviction, not political improvisation.

Why Pardon Cannot Replace Acquittal

Some contributors asked why the issue is not simply resolved by a presidential pardon. The answer is simple:

A pardon assumes guilt.

An acquittal confirms innocence.

A pardon has political implications.

An acquittal has constitutional implications.

And in this case, given the absence of a written law and the tainted process, an acquittal is the only remedy consistent with the Constitution.

So How Do We Critique a Court Judgment?

We critique it with:

the law,

the Constitution,

the record,

the process,

precedents,

and logic.

We critique it respectfully, not abusively.

We critique its reasoning, not its robes.

We critique its omissions, not its existence.

This is not insurrection.

This is democratic vigilance.

Conclusion: Critiquing Courts Protects Democracy, Not Destroys It

The comments from readers were not emotional reactions—they were constitutional questions. They were legal inquiries. They were civic demands for transparency. They represent the highest form of democratic engagement.

Justice must be grounded in text.

Where text is absent, citizens must speak.

Where the process is tainted, citizens must question.

Where the law is ignored, citizens must demand correction.

This is not rebellion.

This is constitutional literacy.

This is civic responsibility.

This is democracy in action.

And in the case of Mazi Nnamdi Kanu, the pathway remains clear:

Release him immediately.

Pursue full acquittal—never pardon.

Then confront the true sponsors of insecurity.