To Kill a Monkey and Abia’s Renewal: From Cinematic Allegory to Governance Revolution

Kemi Adetiba’s Netflix crime thriller To Kill a Monkey (2025) offers a visceral exploration of Nigeria’s systemic failures through protagonist Efemini “Efe” Edewor’s descent into cybercrime. This first-class graduate, driven to criminality by workplace sexual harassment, familial abuse, and desperate poverty, embodies how institutional neglect breeds moral compromise. The series’ title carries layered symbolism: “Killing the monkey” represents both the destruction of one’s ethical foundations for survival and the urgent need to eradicate societal corruption. Through authentic cultural textures like Pidgin English and Urhobo dialects, the narrative exposes how bureaucratic indifference enables criminal networks to thrive, presenting a stark reality where moral compromise becomes survival currency when society abandons its vulnerable.

In Abia State, this metaphor manifests with chilling precision as a legacy of institutionalized looting. Former Governor Theodore Orji and his son allegedly siphoned N521 billion through phantom contracts, diverted security votes, and 100 illicit bank accounts, transforming Nigeria’s “God’s Own State” into a national symbol of decay. This corruption ecosystem birthed crumbling infrastructure, ghost workers, unpaid pensions, and hospitals without medicines, forcing citizens into impossible choices under systems engineered for exploitation. The human cost became visible in roads resembling lunar landscapes and pensioners dying in verification queues, a reality mirroring Efemini’s fictional desperation yet unfolding on a devastating statewide scale.

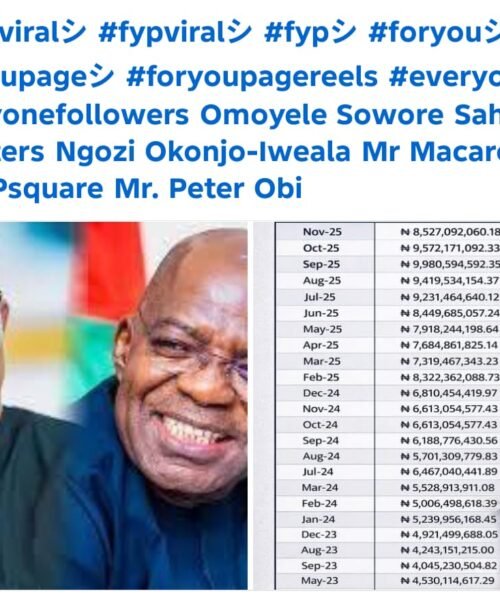

Governor Alex Otti’s administration confronts this “monkey” of corruption through institutional warfare, embodying the antithesis of Efemini’s moral compromise. His transparency offensive—featuring biometric verification and real-time budget tracking—eliminated 23,000 ghost workers and restored regular salary and pension flows, directly reversing decades of civil service rot. Simultaneously, infrastructure functions as tangible justice: the reconstructed Port Harcourt-Umuahia highway erases years of neglect, while the Abia International Airport and Industrial Innovation Park create lawful economic pathways to counter the despair that trapped Efe. These efforts have forged unprecedented cross-party consensus, with former PDP Deputy Governor Ude Oko Chukwu declaring Otti “earned a second term” through intentional governance that transcends partisan divides.

Challenges persist in this unfinished war, mirroring the series’ unresolved tensions. Legal battles against figures like Theodore Orji risk delays reminiscent of Orji Uzor Kalu’s 12-year trial, while systemic resistance from corrupt bureaucrats echoes the institutional complicity depicted in To Kill a Monkey. Managing soaring public expectations requires strategic project distribution across senatorial districts, particularly as citizens who endured Abia’s “ugliness” demand accelerated delivery. Yet Otti’s moral courage in collaborating with EFCC to prosecute past leaders—directly confronting real-world counterparts to the series’ villain “Teacher”—signals an irreversible break from impunity.

The convergence of art and governance crystallizes in Otti’s declaration: “Once we retrieve our state completely, it becomes difficult for people to accept to go back to Egypt.” Where Adetiba’s fiction exposes societal fractures through Efemini’s haunting choices, Otti’s administration demonstrates how integrity rebuilds them—converting stolen billions into roads, airports, and restored dignity. Both narratives affirm that “killing the monkey” begins when moral courage transcends despair, transforming allegory into action that reclaims states and souls alike.

Dr Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke