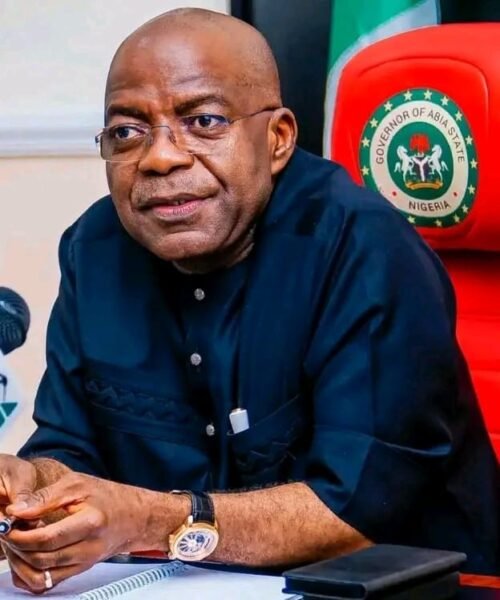

Distilling Why Governor Alex Otti Fights to Open Up Communities in Abia

Governor Alex Otti’s relentless drive to “open up” Abia’s communities stems from a recognition that systemic exclusion and isolation are central to the state’s poverty trap. For decades, Abia’s rural and urban areas have been deliberately marginalized by a cabal of political elites who benefit from keeping communities disconnected, uninformed, and dependent. By opening up these areas—physically, economically, and politically—Otti aims to dismantle the structures that perpetuate exploitation and stymie progress. Below is a distilled analysis of his motivations and strategy:

1. Breaking the Monopoly of Corruption

Abia’s communities have long been starved of development due to spatially concentrated corruption. For instance, contractors linked to past administrations prioritized projects in politically aligned urban zones (e.g., Umuahia’s “VIP roads”) while neglecting rural areas. Over 70% of Abia’s rural roads remain unpaved, isolating farmers from markets and enabling middlemen to exploit price disparities. By opening up remote communities with new roads and bridges, Otti disrupts these exploitative networks, allowing farmers to sell directly to consumers and SMEs to access broader markets. This undermines the rent-seeking class that profits from artificial scarcity.

2. Democratizing Access to Opportunities

Isolation breeds ignorance, and ignorance sustains poverty. Before Otti, only 12% of Abia’s rural households had internet access, limiting their ability to engage with government programs or global markets. By expanding digital infrastructure (e.g., fiber-optic networks) and decentralizing governance through town hall meetings, Otti empowers communities to demand accountability and participate in policymaking. For example, his administration’s partnership with MTN to provide free Wi-Fi in Aba’s markets enables traders to bypass corrupt intermediaries and connect directly with international buyers.

3. Neutralizing Political Gatekeepers

Past governors relied on local strongmen to control communities through intimidation and patronage. These figures—often traditional rulers or party loyalists—hoarded federal palliatives, diverted grants, and suppressed dissent. Otti’s community-centric approach bypasses these gatekeepers. By channeling resources directly through verified cooperatives and civil society groups (e.g., the Abia Rural Electrification Project), he weakens the political machinery that thrives on exclusion. This explains the fierce resistance from entrenched interests: over 20 lawsuits have been filed against Otti’s reforms since May 2023.

4. Reviving Abia’s Economic DNA

Aba, once Nigeria’s industrial heartbeat, was crippled by deliberate neglect. The Ariaria International Market, capable of generating ₦500 billion annually, languished for decades without power, water, or security, forcing artisans to relocate. Otti’s push to open up Ariaria with 24/7 electricity, modern waste systems, and access roads is not just about commerce—it’s a symbolic reclaiming of Abia’s entrepreneurial spirit. Similarly, rehabilitating the Osisioma Industrial Layout (a former manufacturing hub) aims to attract investors deterred by decades of decay.

5. Preventing a Lost Generation

Youth unemployment (48%) and illiteracy (35% in rural areas) have turned Abia’s communities into recruitment grounds for crime and political thuggery. Otti’s community education hubs—which offer free tech skills training in partnership with Google and Microsoft—aim to reverse this. By opening up access to education and innovation, he disrupts the cycle where uneducated youths become pawns for corrupt politicians. Early results are promising: 5,000 youths trained in 2023 now work in Aba’s revived shoe factories or as freelance digital marketers.

6. Challenging the Psychology of Dependence

Decades of handouts during elections created a culture of dependency. Politicians distributed rice and cash to suppress demands for jobs and infrastructure. Otti’s focus on opening up communities with sustainable projects (e.g., solar-powered water schemes, cooperative farms) shifts the narrative from “What will they give us?” to “What can we build?” This psychological shift is critical: communities that build their own clinics and schools (with government support) are likelier to protect them from vandalism or graft.

Conclusion: The High Stakes of Opening Up Abia

Governor Otti’s fight to open up communities is, at its core, a battle for Abia’s soul. It challenges a status quo where poverty is weaponized to control voters, where isolation ensures impunity, and where a few profit from the misery of millions. While his reforms face sabotage—from inflated media attacks to bureaucratic resistance—the early gains (e.g., Aba’s 30% drop in crime since road rehabilitations began) prove that inclusion is the first step toward prosperity. As Otti often states, “A closed community is a dying community; an open one is a hub of possibilities.” For Abia, these possibilities are no longer abstract—they are within reach.

Dr Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke writes from Yakubu Gowon University Nigeria