ABIA 2026: FROM ARGUMENT TO APPROPRIATION — WHEN IDEAS FINALLY BECOME LAW

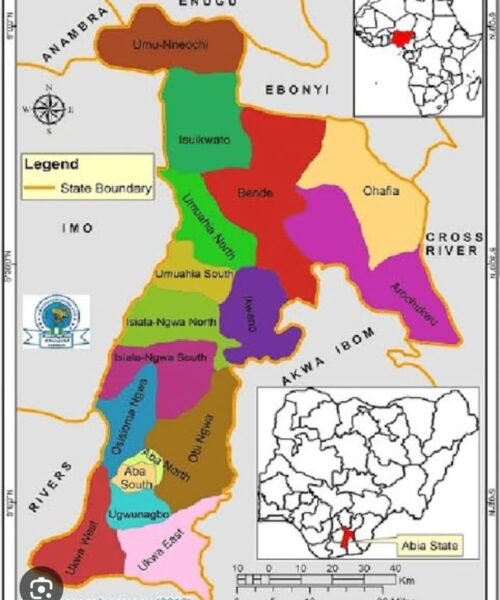

Only days ago, three connected arguments framed the debate about Abia’s future. One warned that Abia’s real struggle was not noise versus silence, but institutions versus personalities. Another situated Abia within a global reform moment, comparing Governor Otti’s posture to learning states that prioritise systems over spectacle. The third insisted that reform becomes real only when ideas survive rhetoric and enter enforceable law.

On December 29, 2025, that debate crossed its first irreversible threshold.

With the signing of the 2026 Appropriation Bill into law by Alex Chioma Otti, Abia moved from argument to codification. Budgets are not speeches. They are legal contracts between the state and its citizens. They bind priorities, constrain discretion, and convert intent into obligation. Whatever one’s politics, appropriation laws are where governance stops being aspirational and becomes testable.

What the Numbers Must Look Like — And Why

While the detailed 2026 breakdown is still being published, Abia’s recent fiscal trajectory provides a reliable analytical base. Between 2023 and 2025, Abia’s approved budgets averaged ₦500–₦560 billion annually, driven by three structural shifts: higher FAAC inflows post-subsidy removal, modest IGR improvements, and increased federal intervention funds. This places Abia’s likely 2026 budget envelope in the ₦550–₦600 billion range, assuming no macroeconomic shock.

From a public-finance efficiency standpoint, international best practice for reforming subnational governments suggests a capital–recurrent ratio of at least 55:45 during infrastructure catch-up phases. Applying this conservatively implies ₦300–₦330 billion in capital expenditure, with ₦250–₦270 billion for recurrent obligations. This balance is critical: underfund capital, and development stalls; overfund it, and payroll arrears and service collapse follow.

Why Capital Allocation Now Becomes Verifiable

What distinguishes the 2026 budget from earlier cycles is not size but structure. Capital spending is no longer defensible without three measurable conditions: identifiable project sites, procurement traceability, and completion timelines aligned to fiscal quarters. A ₦20 billion road programme, for example, becomes economically meaningful only if unit costs fall within Nigeria’s verified ₦800m–₦1.2bn per kilometre urban benchmark, depending on drainage, bridges, and utilities. Anything outside this range demands public explanation.

Similarly, health and education allocations must now be judged by output ratios, not announcements. International development agencies estimate that ₦1 billion in primary healthcare investment, when efficiently deployed, should measurably increase service coverage for 35,000–50,000 residents annually. The 2026 budget therefore exposes whether Abia’s PHC spending is symbolic or scalable.

Revenue Assumptions That Can Be Tested

On the revenue side, conservative modelling suggests FAAC inflows of ₦280–₦320 billion for 2026 if oil production and VAT trends hold. Abia’s IGR, which hovered around ₦30–₦35 billion annually pre-2023, would need to reach ₦50–₦60 billion to signal genuine reform rather than extraction. That increase is only justifiable through base expansion—formalisation of enterprises, land-use charges, and digital compliance—not arbitrary levies.

This is where the budget becomes an accountability instrument. If projected IGR growth exceeds 70–80% year-on-year without structural reforms, it signals optimism bias. If it grows by 25–40% with documented base broadening, it signals institutional learning.

Debt, Deficits, and Fiscal Discipline

Abia’s total debt stock rose modestly between 2022 and 2024, remaining below the 40% revenue-to-debt sustainability threshold recommended by the Debt Management Office. The 2026 budget’s credibility therefore rests on whether new borrowing is tied strictly to capital projects with economic returns, and whether debt-service ratios remain under 20% of total revenue, the red line for subnational solvency.

A deficit-financed capital programme is not inherently reckless. It becomes reckless only when projects lack cash-flow logic or when recurrent spending crowds out debt service. The appropriation law now fixes this risk in black and white.

Why This Budget Ends the Era of Abstract Debate

For critics who insist that Abia lives in press releases, the budget is the answer point. Unlike announcements, an appropriation law fixes numbers to sectors, timelines to programmes, and legal consequences to performance failure. It is the one document that cannot be drowned by applause or outrage.

For supporters, the budget is equally unforgiving. Every claim of “visible and verifiable transformation” must now reconcile with procurement records, contractor performance, and audited outcomes. Visibility without verification will no longer suffice.

From Reform Narrative to Reform Test

There is a deeper political meaning here. By signing the 2026 Appropriation Bill before the year closes, the administration signals fiscal discipline, planning stability, and a move away from improvisation. In subnational economics, predictability lowers risk premiums. Investors, multilaterals, and civil servants read early budgets not as symbolism, but as seriousness.

This moment does not invalidate criticism; it reframes it. The question is no longer whether Abia has plans or visions. The question is whether the 2026 budget will deliver within cost, within time, and within law.

The Line That Has Now Been Crossed

Budgets do not build roads or power hospitals by themselves. But they determine whether those things can be built legally, funded transparently, and audited honestly. That is why this signing matters.

Abia has crossed from argument to appropriation. From persuasion to proof. From rhetoric to rulebook.

Everything else—praise, protest, defence, or dissent—must now respond to one document.

And in any serious democracy, that is exactly how reform is supposed to begin.

AProf Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke