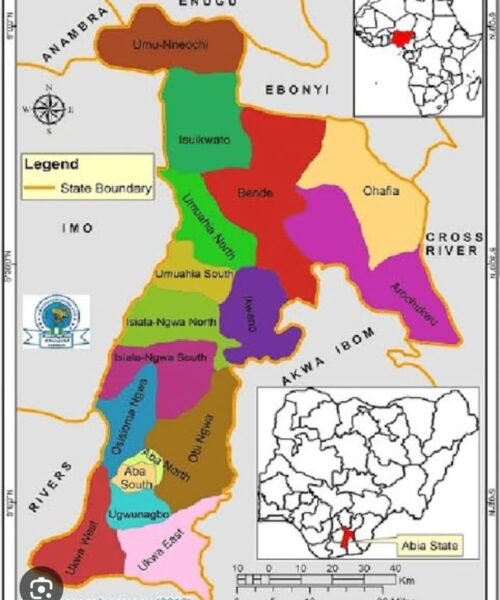

WHY ARE INVESTORS “SCARED” OF THE NEW ABIA? THE FACTS SAY MANY ARE NOT “SCARED” — THEY ARE DOING DUE DILIGENCE

The claim that “serious investors are scared of Abia” sounds dramatic, but it collapses under one basic test: investors don’t make location decisions from skits, hashtags, or abuse threads. They make decisions from governance signals—policy stability, infrastructure trajectory, land and tax administration, dispute-resolution credibility, and whether project sites are visible enough to verify. That is exactly why the loudest online verdicts about “nothing on ground” are not proof of failure; they are, more often, proof of weak civic verification culture and a politics that confuses volume with evidence.

INVESTORS FOLLOW INSTITUTIONS, NOT NOISE

If you want to know what investors consider “serious”, read the World Bank’s own framing: the investment climate is largely an institutional story—how governments reduce risk, enforce rules, and make transactions predictable. Nigeria’s business-enabling reform architecture, supported through frameworks and scorecards, is built around those institutional signals, not propaganda. The World Bank-backed reform logic is explicit: simplify regulation, digitise processes, strengthen land governance, improve dispute resolution, and publish performance to reduce uncertainty. �

Abia State Government

That is the real investor question for Abia: is the state moving from discretionary governance to rule-based governance? On that score, Abia has moved—imperfectly, like every Nigerian state—but measurably, in the direction investors understand.

THE “PRIVATE HOME GOVERNMENT HOUSE” TALK IS POLITICAL THEATRE, NOT AN INVESTMENT METRIC

The claim that governance from a private residence automatically signals “arbitrary decisions” is rhetoric, not an investment standard. Investors care about whether approvals are documented, whether there are clear counterpart agencies, whether contracts are enforceable, and whether disputes can be resolved without mob politics. If anything, the more credible governance test is whether official processes are becoming transparent and auditable—budget performance, procurement discipline, and published reforms—because those are what survive personalities.

Abia’s own public-facing budget performance reporting is precisely the kind of disclosure culture investors watch, because it creates an evidentiary trail that civil society, media, and financiers can interrogate. �

World Bank +1

“NO SINGLE MAJOR INVESTOR” IS A CLAIM WITHOUT A MEASUREMENT BASELINE

Nigeria does not have a clean, universally accepted public dataset that captures “major investors that have located a serious business” at state granularity in real time. That’s why sweeping claims—either “investors are rushing in” or “no investor has come”—are usually political slogans unless they are backed by verifiable instruments such as signed project agreements, disclosed counterparties, operational commissioning records, or independently tracked investment announcements.

A serious argument would cite hard evidence like firm-level registrations, verified industrial tenancy, NIPC disclosures, or audited job creation reports. Where those are missing, honesty requires a narrower claim: “the public has not yet seen enough disclosed, verifiable investor deals.” That is a fair accountability point; the absolutist “none exist” is not.

THE STAR PAPER MILL QUESTION: DUE DILIGENCE DEMANDS DOCUMENTS — BUT THE POLICY LOGIC IS NOT “DESPERATION”

Critics are right to demand a published technical and financial case for any large industrial asset intervention. That is good governance. But the conclusion that “acquiring a moribund asset equals desperation” is not economics; it is narrative. Globally, governments do intervene to unlock distressed productive assets—when they can de-risk the asset, resolve title and legal uncertainty, and crowd in private operators. That “de-risk then crowd-in” model is standard development practice, including in World Bank/IFC-style investment climate reforms. �

Abia State Government

Abia’s burden, therefore, is straightforward: publish the investor pathway, rehabilitation logic, governance structure, and milestones—so citizens can inspect project sites, not arguments.

“ABIA CAN’T STATE GDP” IS A CATEGORY ERROR

States in Nigeria do not routinely publish GDP the way countries do; the national accounts are typically produced at the federal statistical level. Demanding “Abia’s GDP growth rate” as a proof of failure sounds technical but is often misdirected: what citizens should demand instead are measurable state outputs that can be tracked—capital releases vs. project completion, service delivery indicators, IGR performance with methodology, and independently verifiable infrastructure delivery tied to budgets. That is exactly why budget performance reporting matters. �

World Bank +1

ON “SLAPPS”: A DEFAMATION INJUNCTION IS NOT AUTOMATICALLY A HUMAN-RIGHTS ABUSE

If someone says criticism is being silenced “through the courts,” the evidence must show a pattern: repeated suits against multiple critics, disproportionate damages designed to punish public participation, and a strategy of intimidation rather than remedy. One cannot simply declare “SLAPP” as a slogan and call it proof.

In the prominent case now being circulated, the reporting indicates a court granted an interlocutory injunction restraining a named individual from publishing allegedly defamatory content pending determination of a substantive defamation suit. That is a legal process, not a Facebook decree, and it will rise or fall on the merits in court. �

The Whistler Newspaper +1

The pro-democracy position is balanced: defend free speech and public-interest scrutiny and insist that allegations be made with evidence, not name-calling, caricature, or incitement.

THE INVESTOR-READY TEST FOR ABIA IS SIMPLE: SHOW THE PROJECT SITES, THEN SHOW THE PAPER TRAIL

If Abia wants to end this argument permanently, it is not by trading insults with critics. It is by institutionalising verification. Publish the procurement summaries, publish milestone dashboards, publish completion certificates where applicable, publish the investor MOUs and the status of each, and make project sites easy for journalists and citizens to visit. That is how reformist administrations beat cynicism: with auditable proof, not moral arguments.

And for critics who want to be taken seriously by investors, the standard is the same: replace sweeping claims (“nothing exists anywhere”) with site-specific claims (“this project line item says X; I visited the project site at Y on Z date; here is what I found; here are photos; here is the contract reference”). Anything less is politics, not analysis.

CONCLUSION: THE “NEW ABIA” BATTLE IS WON BY EVIDENCE, NOT VOLUME

Investors are not “scared” of media narratives. They are cautious about uncertainty. The way to reduce that uncertainty is what global governance practice has always prescribed: strengthen institutions, disclose performance, reduce discretion, and make verification routine. That is the lane Abia must stay in—and the lane serious critics must also stay in—if Abia is to be judged by facts and project sites, not by digital mobs.

AProf Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke