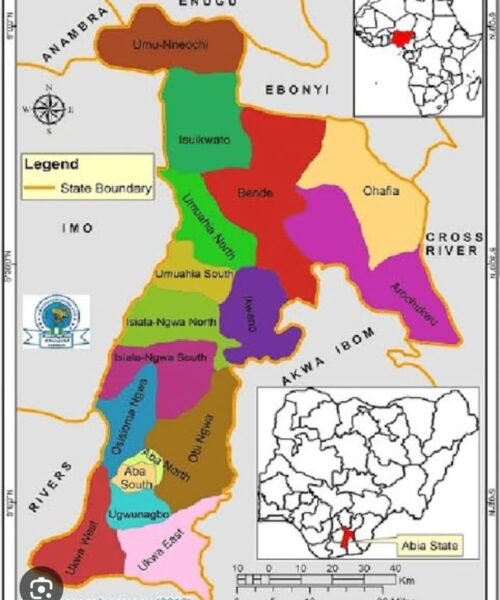

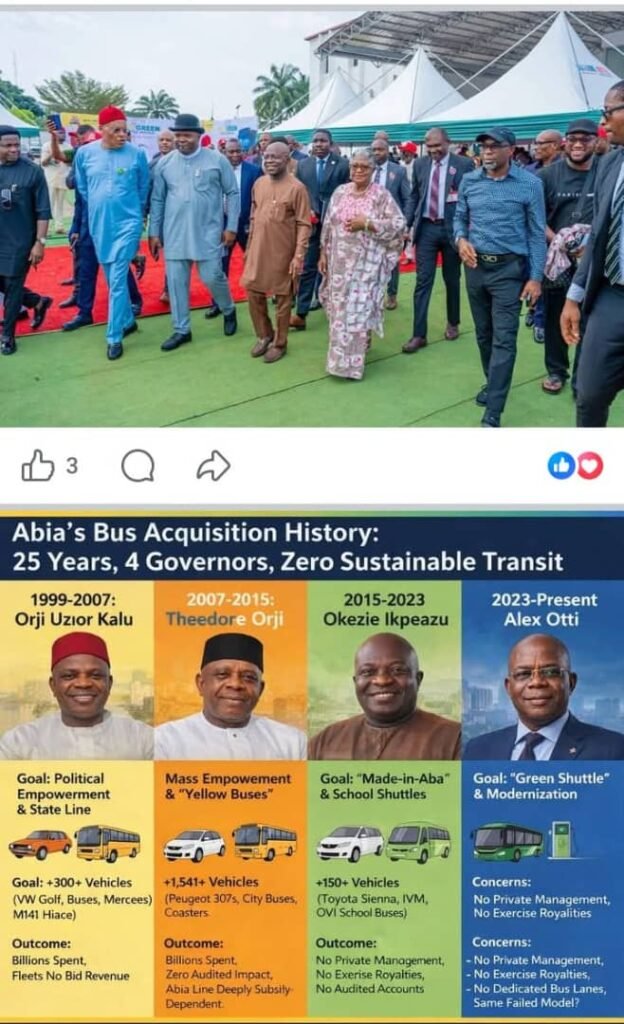

ABIA’S TRANSPORT RESET: HOW GOVERNOR OTTI IS MOVING FROM POLITICAL FLEETS TO A PUBLIC TRANSPORT SYSTEM

For more than two decades, transport policy in Abia State followed a predictable and costly pattern: procure vehicles, announce empowerment, distribute assets, and watch the system collapse. What Governor Alex Chioma Otti is attempting today—despite the noise, cynicism, and deliberate misrepresentation—is a break from that history, not its continuation.

From Ad-hoc Vehicles to Planned Mobility

Unlike previous administrations that treated transport as a patronage tool, the Otti administration has framed mobility as an economic service. The launch of the Abia Green Shuttle is not merely about buses; it signals a shift toward route planning, fleet standardisation, and cost control. Electric buses were not chosen for aesthetics but for lifecycle economics: lower fuel costs, reduced maintenance, and predictable operating expenses over time—an approach consistent with global urban transport reforms.

The World Bank’s Urban Mobility Framework emphasises that sustainable public transport reforms often begin with pilot fleets before scaling infrastructure such as depots, terminals, and dedicated corridors (World Bank Urban Transport Guidance: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/transport). Abia’s phased approach mirrors this logic.

Institutional Thinking, Not Political Distribution

One critical difference under Governor Otti is the refusal to convert public assets into political gifts. Past “work-to-own” and empowerment transport schemes failed because assets were removed from any revenue-tracking framework. Under the current administration, buses remain public assets, routes are structured, and fares are being aligned to operational sustainability—key prerequisites for institutional continuity.

This approach reflects lessons from reforming cities globally. Curitiba and Bogotá did not begin with perfect bus lanes and terminals; they began by enforcing route discipline, centralised scheduling, and transparent fare collection—before scaling infrastructure (UN-Habitat Transport Reports: https://unhabitat.org/topic/transport).

Project Sites and Verifiability

Critics often claim “nothing is on ground,” yet project sites exist and are verifiable:

– Road rehabilitation corridors in Aba that directly support mass transit flow

– Designated Green Shuttle routes already in operation

– Planned charging and maintenance depots disclosed in state planning documents

The difference today is sequencing. Infrastructure is being rebuilt alongside transport reform, not ignored entirely. Development economists consistently warn against the “build everything first” fallacy, noting that systems mature iteratively (OECD Infrastructure Governance Review: https://www.oecd.org/gov/infrastructure-governance).

Fiscal Discipline in a High-Inflation Environment

Nigeria’s post-subsidy fiscal environment has distorted transport economics nationwide. FAAC inflows rose sharply across states after fuel subsidy removal, as documented by Reuters (https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/nigerias-states-reap-windfall-after-fuel-subsidy-cut-2023-10-05/). The question is not whether Abia received more money—every state did—but whether it used that window to reduce recurrent fuel exposure and stabilise service delivery.

By shifting toward electric buses, Abia is insulating part of its transport system from fuel price volatility, a strategy already recommended by international climate-finance and urban-mobility institutions (International Energy Agency EV Transport Outlook: https://www.iea.org/topics/transport).

Why Investors Actually Watch This Closely

Serious investors do not dismiss reform because it is imperfect in year one. They watch for three signals: policy direction, institutional learning, and transparency. Governor Otti’s transport reforms tick two already—direction and learning—and can decisively secure the third through regular public reporting on ridership, costs, and service reliability.

As the African Development Bank notes, “investors price consistency, not perfection” (AfDB Transport Sector Strategy: https://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/sectors/transport).

A Break from the Old Abia Script

The real story is not whether Abia bought buses again. It is that, for the first time in 25 years, a governor is attempting to treat transport as a governed service rather than a political giveaway. That alone marks a structural departure from the past.

Governor Otti’s challenge is execution and disclosure—not intent. If quarterly performance data, audited accounts, and clearly mapped project sites are consistently published, the narrative will inevitably shift from scepticism to validation.

Abia’s transport problem was never a lack of vehicles. It was a lack of systems. For the first time in a generation, the state is at least trying to build one.

AProf Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke