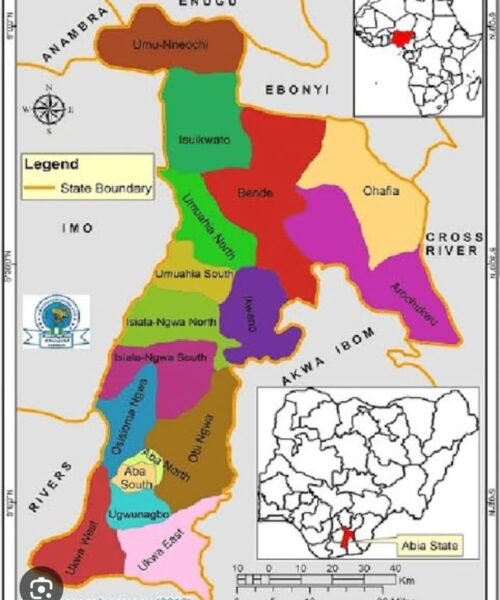

DISINFORMATION, LAWFARE, AND THE GLOBAL ASSAULT ON GOVERNANCE: WHY ABIA’S EXPERIENCE IS PART OF A WORLDWIDE PATTERN

Across the world today, governments are confronting a new threat that does not wear uniforms or seize territory but corrodes institutions from within: organised disinformation amplified by digital platforms and weaponised through political polarisation. From Washington to Brussels, from London to New Delhi, democratic systems are struggling to distinguish legitimate criticism from coordinated falsehood designed to destabilise governance. What is unfolding in Abia State under Governor Alex Chioma Otti is not an anomaly—it is a local manifestation of a global governance crisis.

Internationally, the phenomenon has been well documented. The European Union enacted the Digital Services Act (DSA) in 2023 specifically to curb the spread of coordinated false information and online harassment that undermines democratic processes, noting that unchecked digital abuse “poses systemic risks to public trust and institutional stability” (European Commission, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-services-act-package). The United States has faced similar challenges, with congressional hearings and federal court cases examining how false narratives and online intimidation campaigns distort governance and policy debate (U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee reports, https://www.judiciary.senate.gov).

The United Kingdom has gone even further in framing the issue as a national security concern. A 2024 UK Parliamentary report warned that persistent disinformation campaigns—whether foreign-driven or domestically mobilised—can weaken public confidence in elected leaders and paralyse reformist administrations before results materialise (UK Parliament Intelligence and Security Committee, https://isc.independent.gov.uk). These findings mirror what political economists describe as “narrative capture,” where perception overwhelms evidence.

Abia State now sits squarely within this global trend. Since Governor Otti assumed office, governance debates that should revolve around budgets, audits, timelines, and project sites have increasingly been drowned by viral allegations, caricatures, and emotionally charged claims circulating across social media. Rather than interrogating policy documents or published financial statements, sections of the digital space have adopted the logic of trial by algorithm—where repetition substitutes for proof and outrage replaces verification.

This is not unique to Abia. Reuters has documented how reformist leaders across Africa face similar pressures, noting that “social media has become a primary battlefield where governance credibility is attacked long before institutions can respond” (Reuters, Africa Disinformation Series, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa). In Nigeria specifically, Reuters has reported on how state governments are increasingly forced to balance transparency efforts with the destabilising impact of viral misinformation campaigns (https://www.reuters.com/world/africa).

What distinguishes Governor Otti’s administration is not the presence of criticism—criticism is a democratic constant—but the scale at which false equivalence and narrative manipulation have been deployed. Global governance scholars such as Mariana Mazzucato argue that reformist governments inevitably provoke resistance from entrenched interests, particularly when they attempt to reallocate resources, enforce fiscal discipline, or disrupt opaque systems. In How Nations Learn, Mazzucato notes that “reform governments are most vulnerable during early execution phases, when outcomes lag behind intent and adversarial narratives move faster than institutions” (Penguin Random House, 2024).

This explains why accusations often escalate precisely when reforms begin to bite. In Abia, debates over asset recovery, procurement discipline, and budget restructuring have coincided with intensified digital hostility. The danger, as international experience shows, is that disinformation can delegitimise governance faster than courts, audits, or delivery mechanisms can respond.

Recognising this risk, democratic states globally have begun to draw a line between protected criticism and demonstrably false, defamatory narratives. The doctrine of sub judice, relied upon in multiple common-law jurisdictions, exists precisely to prevent public commentary from prejudicing judicial processes. UK courts, for example, have consistently restrained litigants from running parallel media trials while cases are pending, warning that such conduct undermines justice itself (UK Supreme Court guidance, https://www.supremecourt.uk).

In Nigeria, this principle is firmly established. The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that freedom of expression does not extend to falsehoods capable of causing reputational harm or inciting public disorder, particularly when matters are before the courts (Ideozu v. Ochoma, 2006). These are not authoritarian inventions; they are pillars of constitutional democracy.

Critically, defending institutions against disinformation does not equate to silencing dissent. Transparency International stresses that the antidote to disinformation is not silence but verifiable disclosure—data, audits, procurement records, and independently verifiable project evidence (Transparency International, https://www.transparency.org/en). Where such disclosures exist, disinformation collapses under its own weight.

Governor Otti’s challenge, therefore, is the same challenge confronting reformers globally: governing in an age where perception travels faster than policy. The solution is not withdrawal from public debate, nor indulgence of falsehood, but institutional confidence—anchoring governance in documented facts, audited finances, visible project sites, and rule-based responses to false claims.

Abia’s experience should thus be understood not as local political drama but as part of a global reckoning. Democracies everywhere are learning that governance today requires not only roads, hospitals, and budgets, but resilience against narrative sabotage. Governments that fail to protect institutional credibility collapse under noise. Those that respond with evidence, legality, and delivery endure.

History shows this clearly. From Estonia’s digital governance reforms to Rwanda’s post-genocide institutional rebuilding, reformist administrations that survived disinformation did so by strengthening systems rather than trading insults (World Bank Governance Case Studies, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/governance).

Abia stands at that same junction. The test is not whether criticism exists, but whether truth remains defensible. In this global age of disinformation, defending governance is no longer optional—it is the price of reform.

AProf Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke