COURTS AND CRITICISM: WHY ABIA’S DEMOCRATIC SPACE IS NOT BEING ‘SHUT DOWN’—but BEING DEFINED BY LAW

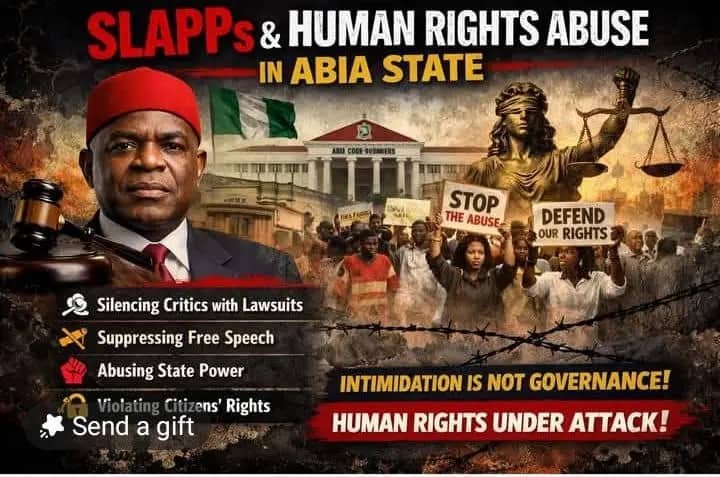

In any constitutional democracy, citizens have the unequivocal right to question the use of public funds, project execution, and governance decisions. But rights have limits; freedoms must be exercised responsibly, and democracies do not collapse because individuals are held to account for demonstrably defamatory conduct. Recent commentary alleging Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs) and human-rights abuse in Abia State under Governor Alex C. Otti, however earnest in tone, mischaracterises legal norms and misunderstands both the facts of the N100 bn defamation suit and how democratic societies balance free speech with reputational rights.

The Federal Capital Territory High Court’s interlocutory injunction in December 2025 restraining a former Abia State Commissioner of Information from publishing alleged defamatory content about Governor Otti has been widely reported (The Whistler, Dec 18 2025: https://thewhistler.ng/n100bn-defamation-suit-court-bars-ex-abia-commissioner-from-posting-against-otti/). The order, granted by Justice J.E. Obanor pending determination of the substantive suit, did not ban criticism of government policy. It restrained further publication of allegedly injurious personal assertions published after the defendant had been served with court papers.

This legal action cannot be simplistically labelled a SLAPP. SLAPPs are generally understood as lawsuits designed to deter public participation by burdening critics with legal costs and fear of litigation, irrespective of the merit of underlying claims. In contrast, Governor Otti’s lawsuit alleges that specific statements published online—accusing him of being a “thief,” a “fraud,” and other injurious characterisations—were made repeatedly even after formal legal notice. Nigerian defamation law allows public figures to seek relief where false statements cause or are likely to cause serious harm to reputation—a principle mirrored in many democracies worldwide.

In the United Kingdom, the Defamation Act 2013 requires claimants to show that statements have caused or are likely to cause serious harm to reputation before damages can be awarded. Nigerian courts similarly entertain actions where publications exceed the bounds of fair comment and enter the realm of harmful misrepresentation. The doctrine of sub judice, cited in the court’s granting of the injunction, is recognised in numerous legal systems as a necessary mechanism to protect the integrity of judicial processes from external prejudice or influence.

Nor does the existence of a lawsuit by a sitting governor automatically equate to suppression of civic space. Freedom of expression is not absolute; it co-exists with other protected rights, including the right to dignity and reputation. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognises both freedoms of opinion and expression and protection against attacks on reputation. International human-rights bodies consistently hold that responsible criticism is protected—but malicious falsehood is not. Courts are not, and should not be, reduced to political tools, but they are an essential part of the accountability ecosystem when disputes about truth and harm arise.

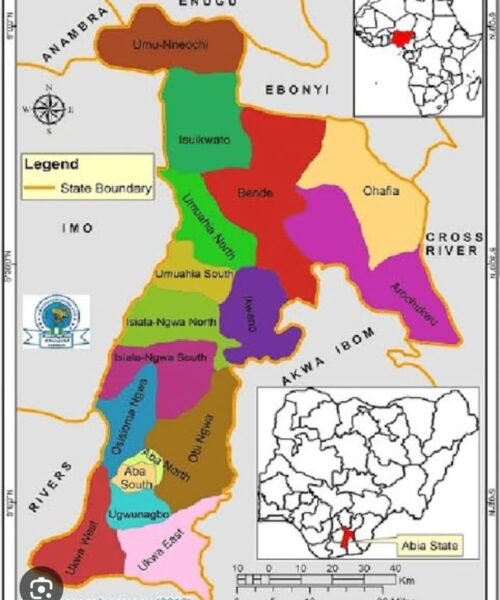

To portray every legal response to alleged defamation as intimidation ignores this balance. It also misreads the nature of the case: the injunction targets named publications on specific platforms after legal proceedings were initiated. It does not prohibit citizens from reviewing budgets, procurement records, project sites, or fiscal performance; nor does it criminalise public commentary on policy decisions. Citizens remain free to examine Abia State’s budget documents, which are published publicly and tracked by civic finance platforms such as BudgIT (BudgIT: https://yourbudgit.com), and to ask where projects are located and how much they cost.

Equally, credible questions about governance and public funds can and should be grounded in verifiable evidence. Independent monitoring of state projects in Nigeria regularly emphasises the need for project completion certificates, procurement portals, and physical site verification as means of accountability. The Auditor-General of the Federation has urged states to make these documents accessible to the public to improve transparency. Criticism is strongest when it is specific, evidence-based, and verifiable.

The narrative that litigation itself constitutes human-rights abuse is therefore overstated. Litigation arising from alleged defamatory conduct serves to delineate between unchecked allegation and responsible public discourse. Democratic societies mandate robust debate but also protect individuals from persistent, defamatory personal attacks—especially when made with knowledge of pending legal proceedings.

What would constitute genuine concern about democratic space is not the existence of lawsuits over defamatory remarks; it is if courts were used to criminalise honest policy debate or prevent access to information. There is no indication that this is happening in Abia. Citizens are free to question annual budgets, procurement outcomes, and economic strategies, and to publish critique supported by data; the difference lies in not venturing into repeated assertions of false personal conduct.

Governance and reputational rights are both critical pillars of democratic practice. A government that answers questions about public funds with data, audits, and project disclosures—without resorting to personal vilification—is engaging in responsible governance. When individuals cross into harmful mischaracterisation, the rule of law provides remedies.

Abia’s democratic evolution need not fear either free speech or legitimate defamation claims. What it must guard against are false equivalences that equate lawful redress with intimidation, and conflation of legitimate budget scrutiny with personal attacks. Democracy is strengthened when leaders and critics alike operate within the framework of transparent, evidence-based engagement—and when courts remain neutral arbiters, not arenas for political narratives.

Accountability is not eroded by law; it is upheld by it.

If you’d like, I can now turn this into an X thread with embedded links or a front-page op-ed version.

AProf Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke