COURTS, CRITICISM, AND ACCOUNTABILITY IN ABIA: DEFENDING DEMOCRACY, NOT SILENCING IT

In every constitutional democracy, courts exist to protect rights, restrain excesses, and provide neutral forums for resolving disputes. When citizens ask hard questions about governance, they should never face intimidation—but equally, public office holders have every right to protect their reputations under the law when falsehoods cross into defamation. In Abia State, the recent N100bn defamation suit filed by Governor Alex Chioma Otti does not signal a crackdown on dissent; it underscores a deeper, under-reported truth: democracy requires both scrutiny and restraint.

On December 18, 2025, a Federal Capital Territory (FCT) High Court granted an interlocutory injunction restraining a former Abia State Commissioner of Information, Barr. Eze Chikamnayo, from publishing defamatory content against Governor Otti pending substantive suit proceedings (Whistler, Dec 18, 2025: https://thewhistler.ng/n100bn-defamation-suit-court-bars-ex-abia-commissioner-from-posting-against-otti/). Justice J.E. Obanor ordered that Chikamnayo must cease posting allegedly offensive material on his Facebook page and other platforms until the case is fully heard. The court also adjourned the next hearing to January 19, 2026.

Critics have framed this case as “intimidation.” But a close reading of the lawsuit shows it is not a blanket gag order on criticism. Defamation suits exist in democracies precisely to balance freedom of speech with protection from malicious falsehoods. In the UK and other common-law jurisdictions, public figures regularly seek redress where false statements cause reputational harm and social instability. Nigeria’s legal framework also recognises that malicious misrepresentation—especially when repeated after notice of legal action—can be actionable.

Governor Otti’s legal team, led by Senior Advocate of Nigeria Dr. Sonny Ajala, argued that Chikamnayo continued to publish alleged defamatory posts after being served court papers on October 17, 2025. According to court documents, those posts went beyond policy critique into personal attack, including repeated claims that the governor is a “thief” and “fraud,” language the plaintiff’s lawyers characterized as “offensive” and injurious to reputation (Whistler, Dec 18, 2025). The affidavit supporting the motion emphasised that such publications could cause “irreparable reputational damage” and potentially incite unrest while the matter remains sub judice.

Legal experts note that courts routinely intervene where ongoing publications risk prejudicing judicial processes or escalating conflict. The doctrine of sub judice—which forbids public acts that may influence pending judicial proceedings—is recognised in many jurisdictions and aims to preserve the integrity of the justice system. Governor Otti’s counsel cited this doctrine in arguing for the interlocutory order (Whistler, Dec 18, 2025).

Importantly, the action is not against criticism of public policy. It targets allegedly unverified personal attacks made even after formal notice was served. In democracies around the world, criticism of governance, budgets, project delivery, and public offices is not just tolerated but encouraged. Yet the law draws a line when statements stray into false allegation, especially against individuals whose primary public identity is their elected role. As the Supreme Court has noted in similar contexts, the threshold for restraining publication is not hostility to free speech but protecting the rule of law and individual reputation pending adjudication.

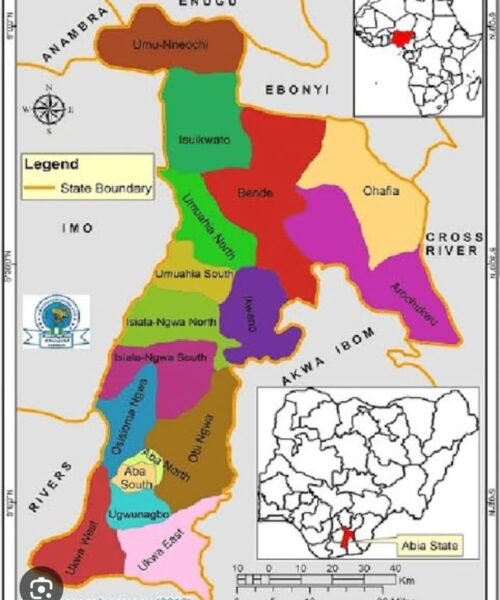

The broader context matters. Abia under Governor Otti has not shied away from transparency on fiscal matters. Civic finance monitors such as BudgIT have documented improved public budget disclosures and fiscal reporting (BudgIT Open States Portal: https://yourbudgit.com). Independent healthcare rankings placed Abia among leading states in primary healthcare performance, citing public data and programme outcomes. These are substantiated improvements tied to measurable indicators, not mere rhetoric—precisely the kinds of evidence-based scrutiny that strengthen governance, not weaken it.

Meanwhile, the Whistler report makes clear that the suit seeks not just injunctive relief but a legally adjudicated separation between verifiable criticism and unverified personal claims. If the substantive suit proceeds and the evidence supports the governor’s claim of reputational injury, the court may order damages and corrections; if not, the case will be dismissed. That is how the rule of law operates, whether in Nigeria, the UK, or the US. In the UK, the Defamation Act 2013 similarly requires claimants to show serious harm to reputation before damages are considered. Courts there have restrained publication when harms are substantial and ongoing (UK Defamation Act: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2013/26/contents/enacted).

The narrative that this lawsuit represents a broad assault on public questioning collapses under scrutiny. If anything, it highlights the difference between legitimate public debate and harmful defamation. Democracies thrive not on unfiltered publication but on responsible discourse, where criticisms are evidence-based and where falsehoods can be corrected under law, not amplified unchecked.

Governance is measured by outcomes—factually documented budgets, audited project sites, economic indicators—not by gladiatorial social media clashes. When citizens raise questions about public funds, the government should and does respond with data, planning documents, and performance reports. When individuals resort to repeated personal accusations that may mislead rather than inform, courts exist to arbitrate, not to intimidate.

History shows that democracies are strengthened when the rule of law is applied impartially: protecting citizens’ rights to speak and to seek redress when speech crosses into defamation. Abia’s political evolution will be best served not by silencing disagreement, but by insisting that disagreements be grounded in verifiable facts and accountable frameworks.

In the end, free speech and reputational rights are not opposites. They are complementary pillars of democratic governance—both essential, both protected, both necessary for a stable, transparent society.

AProf Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke