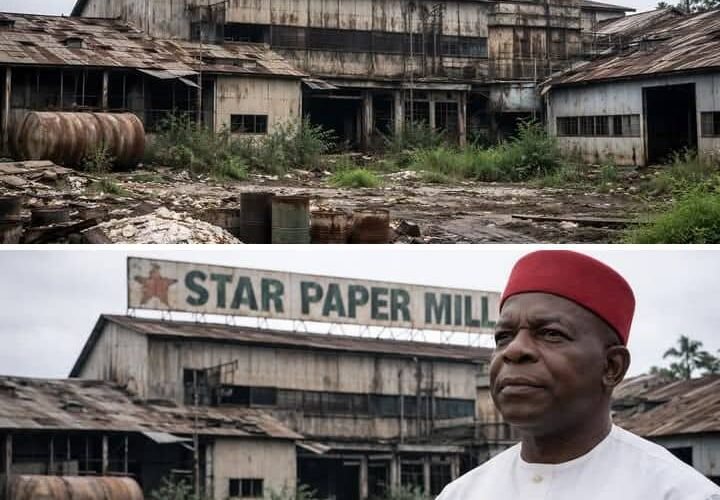

Abia’s Star Paper Mill

The critique by Eke O. Ako presents itself as a technical interrogation, but a closer reading reveals that it conflates unanswered public curiosity with absence of due diligence, and substitutes speculation for evidence. In public-sector investment, particularly asset recovery from insolvency managers such as AMCON, the absence of a publicly released white paper does not equate to the absence of technical, financial, or legal work. In fact, AMCON’s entire statutory mandate under the AMCON Act of 2010 requires valuation, asset integrity assessment, creditor resolution, and risk containment before any transfer of distressed assets can occur. The suggestion that Star Paper Mill was “acquired” casually or without rigorous scrutiny misunderstands how AMCON transactions legally function in Nigeria.

Star Paper Mill was not a greenfield gamble; it was a distressed industrial asset under federal custodianship. Any handover necessarily followed asset verification, title clarification, debt reconciliation, and residual value assessment, processes that have been repeatedly documented in AMCON-managed recoveries across Nigeria, including the takeover and re-privatisation of assets such as Eko Hotels shareholdings, Aero Contractors, and Daily Times. To imply that Abia State could simply “siphon funds” through an AMCON-supervised transaction ignores both federal oversight and the paper trail inherent in such recoveries.

The critique further assumes that the Abia State Government intends to operate Star Paper Mill directly, yet Governor Alex Otti has repeatedly and explicitly stated the opposite. His policy framing aligns with modern development-state practice: government as de-risker, not operator. This model is not experimental. It is consistent with the asset-recovery and concession frameworks used in Malaysia’s Khazanah Nasional, Singapore’s Temasek-linked industrial turnarounds, and even Nigeria’s own Lekki Deep Sea Port structure, where public intervention stabilised assets before private capital assumed operational risk. Evaluating Star Paper Mill as if it were a conventional state-owned enterprise revival therefore misrepresents the policy intent.

On technical obsolescence, the argument assumes that age automatically negates economic value. That assumption is flawed. Paper mills globally operate on long asset lives because core equipment is modular, upgradeable, and often rehabilitated in phases. What matters is not the manufacturing date of machinery but the cost curve of rehabilitation relative to market demand. Nigeria currently imports over 60 percent of its paper and paperboard needs, according to data from the National Bureau of Statistics and industry trade reports. Any serious feasibility assessment would therefore benchmark local production against import substitution opportunities, logistics savings, and currency risk mitigation. These are precisely the variables that attract private partners once institutional and title risks are resolved.

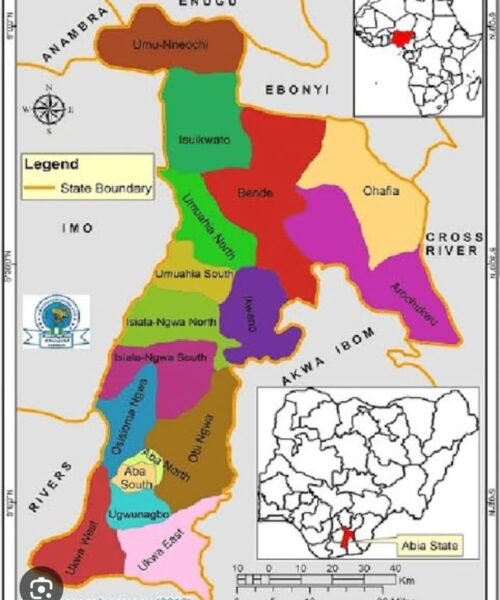

The critique’s emphasis on “opportunity cost” is legitimate in theory but incomplete in application. Opportunity cost is not evaluated in isolation from asset specificity. Star Paper Mill is not merely land and scrap; it is a strategically located industrial site in Aba with sunk infrastructure, historical supply chains, and labour memory. Greenfield alternatives such as agro-parks or recycling clusters are not substitutes but complements. Development economics literature, from Ha-Joon Chang to Robert Bates, is clear that late-industrialising regions recover faster when they reactivate dormant productive assets while simultaneously building new ones. The argument that only one path should be chosen is a false dichotomy.

On governance safeguards, the assertion that there are “no milestones” or “no performance thresholds” again confuses non-publication with non-existence. Public-private transition frameworks typically embed milestones within concession and management agreements, not press releases. The presence of ACCIMA, UCCIMA, AMCON, and prospective investors in the handover process strongly indicates a structured transition rather than an open-ended fiscal drain. Moreover, Abia State’s recent fiscal transparency record, including quarterly budget performance publications, weakens the claim that this decision sits outside any value-for-money framework.

The historical comparison to failed government industrial interventions also requires nuance. Most failures cited from the 1980s and 1990s occurred under import-substitution regimes marked by price controls, politicised management, and zero private-sector participation. Star Paper Mill’s recovery is occurring under a different macroeconomic and institutional logic: liberalised markets, PPP frameworks, independent procurement oversight, and investor-led operations. To apply yesterday’s failure models to today’s governance structure without adjustment is analytically lazy.

Finally, the charge that this intervention is “mere publicity” collapses under basic scrutiny. Publicity stunts do not involve refunding prior purchasers, negotiating with federal recovery agencies, committing multi-year industrial policy capital, or inviting chambers of commerce to assume operational leadership. Optics are cheap; institutional repair is expensive. The Abia State Government has chosen the latter.

Scepticism is healthy in public finance, but scepticism must be evidence-driven. What is missing from the critique is not passion but proof: no counter-valuation, no alternative feasibility study, no data disproving market demand, no evidence of procedural breach. Until such evidence is presented, the Star Paper Mill recovery remains what it appears to be—an orthodox development-state intervention grounded in asset recovery, risk de-escalation, and private-sector-led revival.

The appropriate conclusion, therefore, is not that Abia has made a “poor strategic decision,” but that the state has embarked on a high-discipline, high-coordination industrial recovery whose success will be judged not by rhetoric but by execution. Prudence demands scrutiny. Seriousness demands accuracy.

AProf Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke