Aba Women: From Historic Rebellion to Contemporary Socio-Political and Economic Powerhouse (1929-2025)

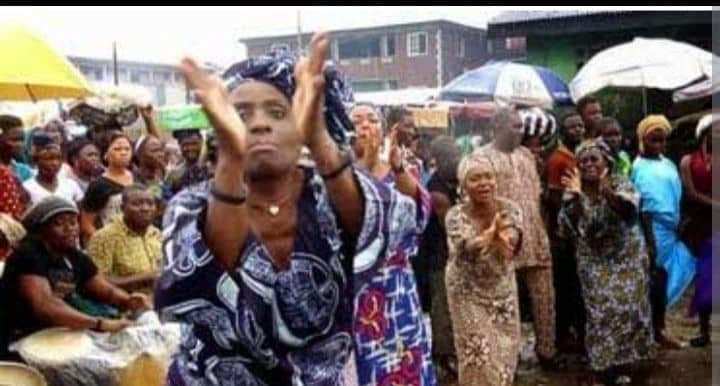

The Aba Women’s War of 1929 ignited as a direct response to British colonial oppression, specifically the threat of women’s taxation and abuses by imposed “Warrant Chiefs.” Sparked by Nwanyeruwa’s defiance of a census enumerator in Oloko, the movement rapidly mobilized thousands of women across southeastern Nigeria using the traditional protest tactic of “sitting on a man” (Ogu Umunwaanyi). Despite violent colonial suppression resulting in over 50 deaths, the rebellion succeeded in abolishing the proposed women’s tax and dismantling the despised Warrant Chief system, cementing its legacy as a landmark event in anti-colonial and feminist resistance globally.

In the decades following Nigerian independence (1960-2000), Abia’s women solidified their role as economic powerhouses, particularly dominating Aba’s vibrant markets like Ariaria and pioneering the resilient “Aba Made” brand in small-scale manufacturing, textiles, and footwear. However, their translation of economic influence into political power faced significant hurdles due to entrenched patriarchal norms, the rise of costly and violent “money politics,” and a lack of institutional support or affirmative action within political parties.

By 2025, Abia women remain critically underrepresented in formal politics despite persistent advocacy. They hold fewer than 10 percent of State Assembly seats, with Local Government Chair positions remaining exceptionally rare. Tokenistic appointments, such as the recurring Commissioner for Women’s Affairs role, often limit broader influence, while barriers like cultural bias (affecting 61% of women), financial constraints (61%), electoral violence (61%), and educational gaps persist. Economically, they continue to drive Aba’s commercial and industrial engine, leading SMEs in garment manufacturing, leatherworks, and trade. However, they grapple with poor infrastructure, multiple taxation, limited access to formal credit, and competition from imports. Socially, female literacy rates show improvement (around 62% for young women), empowering rights awareness, but Gender-Based Violence and harmful traditional practices remain serious concerns. The success of the Greater Aba Development Authority (GADA) initiative is pivotal for addressing critical infrastructure needs that directly impact women-led businesses.

Moving forward, realizing the full potential embodied by the 1929 legacy requires decisive action. Political empowerment necessitates implementing strict gender quotas (e.g., 35% candidate mandates), combating money politics and violence through electoral reforms and security, and moving beyond token appointments to support women in substantive portfolios. Economically, enhancing finance access through tailored credit schemes, investing decisively in infrastructure via GADA, supporting the “Aba Made” brand with quality control and market access, and aiding business formalization are crucial. Socio-culturally, sustained grassroots education challenging gender stereotypes, rigorous enforcement of GBV and inheritance laws, and continued investment in girls’ education are imperative. The revolutionary spirit of 1929 thus endures – a testament to enduring courage and socio-economic resilience – but the struggle for equitable political representation and unconstrained economic opportunity remains unfinished in contemporary Abia State.

Dr Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke writes from the University of Abuja Nigeria