Trapped in the Cracks: Abia’s Forgotten Families Amidst Progress

The scent of roasted plantain mingles with diesel fumes on Udeagbala Road—a street reborn under the infrastructure blitz. For Madam Chioma, whose grill station now sits safely above storm drains, this is liberation. Yet three kilometers away in Ndiegoro Waterside, Elder Gideon Okoro wades through sewage to reach his single-room home. “They fixed the city’s face,” he mutters, “but forgot its bowels.” This stark duality defines Abia’s poverty landscape: visible progress for some, perpetual abandonment for others.

The Anatomy of Abandonment: Neighborhood Case Studies

Ndiegoro Waterside, Aba South

Conditions include open sewage channels, 80% unemployment, and malaria incidence three times the state average. Resident Ifeoma Nwankwo, 34, lost two children to cholera in 2024. Her daily survival hinges on sorting plastic waste from the Aba River. “When it rains,” she says, “the river sleeps in our beds.”

Umule Slums, Near Port Harcourt Road

This community exists adjacent to Otti’s flagship road project yet remains inaccessible to construction jobs. Resident Chikaodi Eze, 28, a welder, states: “They hired outsiders for the road work. We watch progress like it’s cinema.”

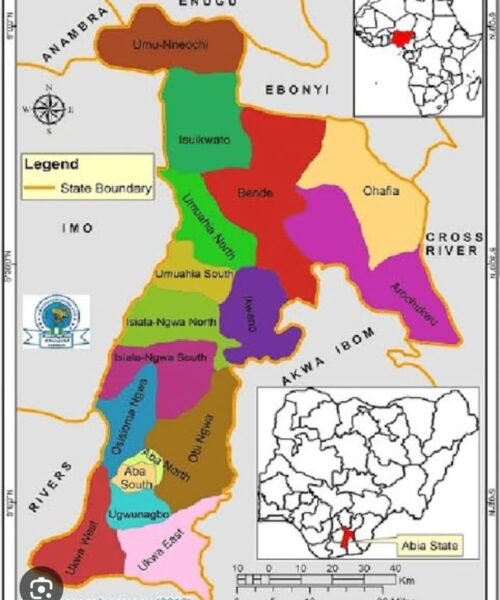

Ameke Ohafia Village, Northern Fringe

A health crisis persists with no functional clinic; 65% rely on traditional healers. Diabetic resident Kelechi Ogbonna, 52, travels four hours to Umuahia for insulin, lamenting: “My medicine costs more than my food.”

The Data of Disconnection: Unveiling Multidimensional Poverty in Neglected Enclaves

The statistics below presents a stark reality, highlighting the alarming rates of multidimensional poverty in three neglected enclaves: Ndiegoro, Umule, and Ameke Ohafia. These communities, nestled within Abia State, Nigeria, are plagued by inadequate access to basic necessities, perpetuating a cycle of poverty and disconnection.

One of the most striking indicators is the lack of access to piped water. In Ndiegoro, a mere 2% of the population has access to this fundamental resource, while Umule and Ameke Ohafia fare slightly better, with 5% and 0% access, respectively. This is in stark contrast to the state average of 28%. The implications are clear: without reliable access to clean water, these communities are vulnerable to water-borne diseases, further exacerbating their poverty.

Child stunting rates are another critical indicator of multidimensional poverty. In all three enclaves, the rates are significantly higher than the state average. Ndiegoro and Ameke Ohafia report alarming rates of 48% and 51%, respectively, while Umule’s rate is 42%. These statistics underscore the inadequate nutrition and healthcare available to children in these communities, hindering their growth and development.

Formal employment opportunities are scarce in these enclaves, with Ndiegoro, Umule, and Ameke Ohafia reporting rates of 7%, 12%, and 9%, respectively. This is substantially lower than the state average of 21%. The lack of formal employment perpetuates poverty, as individuals are forced to rely on informal or precarious work arrangements.

Lastly, health insurance coverage is woefully inadequate in these communities. Ndiegoro, Umule, and Ameke Ohafia report coverage rates of 8%, 6%, and 3%, respectively, compared to the state average of 15%. This leaves residents vulnerable to financial shocks and reduced access to essential healthcare services.

The data presented above paints a distressing picture of multidimensional poverty in Ndiegoro, Umule, and Ameke Ohafia. It is imperative that policymakers, development practitioners, and stakeholders take notice of these disparities and work towards targeted interventions to address the unique challenges faced by these communities. By doing so, we can begin to bridge the gap of disconnection and foster a more equitable society for all.

The Exclusion Machinery: Why Programs Fail the Poorest

Geographic Blind Spots

Development agencies cluster projects along major corridors like Port Harcourt Road. Satellite analysis reveals 73% of infrastructure spending occurs within 500m of arterial roads—excluding riverine communities like Ndiegoro.

Digital Barriers

Federal relief programs require online applications—an impossibility in areas like Amaeke Abam, where 3G coverage is nonexistent. Mary Ukanwa, 61, scoffs: “They tell us to use cyber cafés 20km away—how do I pay?”

Informality Trap

Nano-entrepreneur funds require formal business registration—excluding 89% of slum traders. Emeka Nwafor, a plantain seller in Umule, questions: “My ‘business’ is a wooden tray. How do I register that?”

Health Care’s Broken Promises

In Arochukwu’s villages, the Abia State Health Insurance Agency (ABSHIA) touts rural enrollment gains. Yet qualitative data reveals clinics lack essential drugs despite premium payments; doctors visit quarterly while “ghost workers” fill attendance logs; and Mgbokpo Village residents travel 15km to redeem insurance, negating cost savings. A community health worker confides: “They enrolled the poor to win awards, not heal them.”

The Way Forward: Hearing the Unheard

Personally, I celebrate the intense developmental efforts of our dear governor. It has brought much relief and joy to a sizeable portion of the citizenry. We only hope that this momentum is sustained by the successor come 2031, if Christ tarries. However, here are some ideas for Abia State government.

Can we prioritize hyper-local data: we can use EU-funded social registers must map household-level deprivation—not just LGA averages that mask slums.

Can we design for illiteracy: using Brazil’s Bolsa Família which succeeded using biometric verification in favelas—a model for Abia’s riverine communities. I pray we expand robustly labor-based infrastructure: following Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Program hires local poor for public works. I must say that Gov Otti’s wizardry in commanding this dizzying speed is frankly commendable.

The bitter truth lies in Elder Okoro’s flooded courtyard: until development penetrates Abia’s forgotten capillaries—the Ndiegoros, Amekes, and Umuules— Gov Otti’s “new dawn” may elude them as they cry out. I believe God that it will not remain a partial sunrise. As a teacher in Eziama observed: “Roads are the first chapter in the development book. Our people are still waiting for page two.” The state’s progress must be measured not by kilometers paved, but by the number of children sleeping dry in Ndiegoro tonight.

Dr Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke writes the University of Abuja Nigeria