JAMB Jolt: 70% Fail, 0.63% Excel – Why Abia’s Brightest Still Can’t Escape the Quota Trap

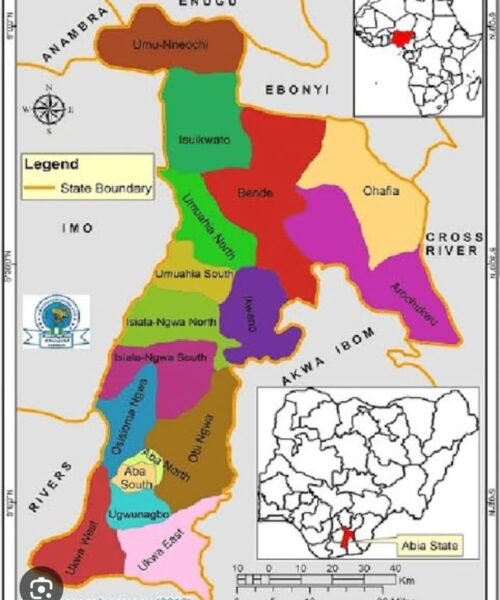

The 2025 JAMB results have intensified discussions about Nigeria’s educational challenges, particularly the widening gap between academic performance and equitable access to tertiary institutions. Out of 1.9 million candidates who took the UTME, over 70% scored below 200, with only 0.63% achieving scores above 300. This trend mirrors previous years, such as 2023, when just 27% of candidates surpassed the 200 mark. While systemic issues like uneven resource distribution and curriculum misalignment contribute to these outcomes, the situation in Abia State adds another layer of complexity. Despite consistently ranking among the top performers in national exams like WAEC and JAMB, students from Abia face significant hurdles securing admissions to federal universities outside their state. This paradox stems from Nigeria’s federal quota system, which prioritizes catchment areas and educationally disadvantaged regions, often forcing high-achieving Abia candidates to compete for a limited pool of merit-based slots. For instance, a student from Abia might require a JAMB score 20–30 points higher than a peer from a university’s catchment area for the same course, despite comparable academic rigor in their secondary education.

Governor Alex Otti’s administration has responded by prioritizing local educational infrastructure. Initiatives include appointing new leadership at institutions like the Abia State College of Health Sciences to improve accreditation standards and launching probes into examination malpractice at state-run nursing schools. These efforts aim to retain talent within Abia’s tertiary institutions and reduce reliance on federal admission slots. However, broader structural reforms remain critical. The Federal Ministry of Education’s quota system, though designed to promote national unity, often sidelines merit in favor of geographic equity. For example, while the national JAMB cut-off is 180, competitive courses like Medicine or Engineering in federal universities unofficially require 250+ for candidates from non-catchment states like Abia. This creates a bottleneck where even high-performing students struggle to secure placements, exacerbating brain drain and underutilization of academic potential.

To address these disparities, Dr Alex Chioma Otti OFR proposes multi-level interventions as Abia State expands its tertiary institutions through public-private partnerships, easing admission pressure. Simultaneously, some other concerned Abians in support of the numerous efforts of the Otti administration, pray that federal policymakers might have to recalibrate the quota system to reserve a larger percentage of slots for purely merit-based admissions, ensuring high-scoring candidates from all states have fair opportunities. Personally, I applaud the new initiatives in Abia State as regards Teacher training programs and JAMB-aligned curriculum reforms in secondary schools could also improve baseline performance.

Ultimately, the 2025 JAMB results underscore a critical need for collaboration between state and federal actors. While Abia’s local reforms are commendable, lasting progress hinges on national policy shifts that balance equity with merit, ensuring academic excellence is rewarded regardless of geographic origin. Without such changes, Nigeria risks perpetuating cycles where educational potential is stifled by systemic inequities rather than academic capability.

Dr Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke writes from Yakubu Gowon University Nigeria