Human Capital Development in Abia State, Nigeria: *A Microeconomic Analysis

Abia State, situated in southeastern Nigeria, embodies a microcosm of the nation’s human capital challenges and opportunities. Known for its entrepreneurial energy, particularly in cities like Aba—a bustling hub for commerce and small-scale manufacturing—the state grapples with systemic barriers rooted in economic decision-making, cultural norms, and institutional shortcomings. A microeconomic lens reveals how individual and household choices, shaped by costs, benefits, and constraints, intersect with broader structural inefficiencies to shape human capital outcomes.

At the core of Abia’s human capital dynamics lies Human Capital Theory, which posits that investments in education and health yield long-term economic returns. In practice, households weigh immediate financial burdens—such as school fees, uniforms, and the opportunity cost of children’s labor—against uncertain future benefits. Rural communities like Umunneochi, where subsistence farming dominates, often prioritize short-term income over schooling, exacerbated by liquidity constraints and limited access to credit. Even in urban centers like Aba, skepticism about education’s value persists due to youth unemployment rates, which exceed national averages. Parents question the return on investing in tertiary education when formal-sector jobs remain scarce, pushing many toward informal trades.

The Household Production Model further illuminates gender disparities in human capital allocation. While Abia’s gender gaps are less pronounced than in northern Nigeria, cultural expectations still steer girls toward early marriage or informal trade, while boys are encouraged to pursue technical skills. In Ariaria Market, a landmark for leather and garment production, adolescents often join family businesses instead of completing secondary education—a trade-off that sacrifices long-term skill development for immediate income. This pattern perpetuates intergenerational cycles of underemployment, limiting productivity gains in Abia’s industrial sectors.

Signaling Theory underscores another paradox: despite rising university enrollment, credentials like degrees from Abia State University often fail to translate into formal employment. Employers in Aba’s manufacturing sector increasingly prioritize practical skills over academic qualifications, rendering tertiary certificates weak signals of productivity. This mismatch has fueled underemployment, with graduates resorting to low-wage informal jobs that underutilize their education. Meanwhile, the proliferation of degree holders has not spurred corresponding job creation, deepening disillusionment with higher education.

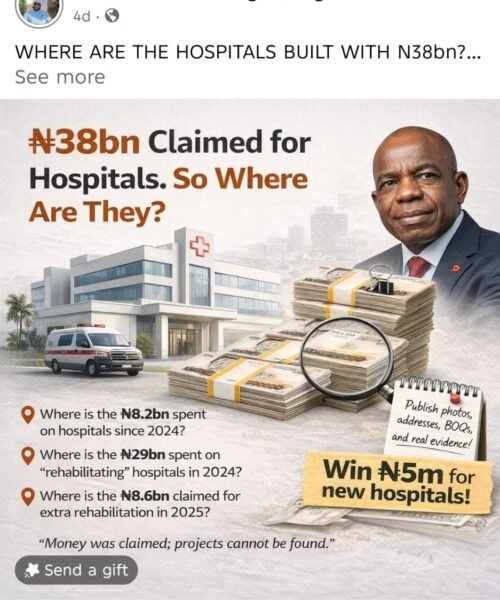

Institutional Economics reveals how weak governance exacerbates these challenges. Abia’s public schools, particularly in rural regions like Ohafia LGA, suffer from dilapidated infrastructure, teacher strikes over unpaid salaries, and overcrowded classrooms. Healthcare access is similarly fragmented: only 12% of residents have health insurance, and rural clinics lack essential drugs and equipment. Urban centers like Umuahia fare better, but the urban-rural divide perpetuates inequities in health and education outcomes. Corruption further strains resources, with mismanaged local funds delaying school renovations and clinic upgrades.

Abia’s education sector reflects both progress and stagnation. While 68% of children enroll in primary school, dropout rates spike at the secondary level, especially among rural girls. Curricula remain misaligned with the state’s economic strengths, such as leatherworks and textiles, leaving graduates unprepared for self-employment or technical roles. This skills mismatch stifles innovation in sectors where Abia holds competitive advantages.

In healthcare, malaria accounts for 40% of hospital visits, draining productivity and compounding poverty. Maternal mortality remains alarmingly high at 512 deaths per 100,000 births, with rural women disproportionately affected due to limited access to prenatal care. The Abia State Telehealth Initiative, which deployed mobile clinics in partnership with local leaders, reduced maternal deaths by 18% in pilot areas—a model that could scale with sustained investment.

The labor market is dominated by informality, with over 85% of jobs concentrated in Aba’s markets and small-scale manufacturing. Even skilled artisans earn meager wages due to limited access to modern tools and credit. Underemployment persists despite Abia’s growing tech sector, which remains untapped due to risk aversion and lack of targeted training.

Gender dynamics further complicate human capital development. Women dominate informal trade but face barriers to scaling businesses, including cultural biases in loan access and property rights. Initiatives like market women cooperatives have begun addressing these gaps by providing microloans, yet systemic change requires broader legal and cultural shifts.

Microeconomic barriers, such as market failures and behavioral constraints, underpin these challenges. Positive externalities of education—like reduced crime and improved public health—are overlooked by households focused on private returns. Information gaps further distort decision-making: many parents remain unaware of vocational programs like the National Directorate of Employment’s schemes in Aba. Present bias drives poor families in regions like Isuikwuato to prioritize daily survival over education savings, while risk aversion deters university investment despite emerging opportunities in tech.

Empirical insights, coupled with the government’s resolve to change the narrative highlight pathways for progress. The Aba Leather Cluster program, which trains youth in modern shoemaking techniques, boosted participants’ incomes by 35%, demonstrating the potential of industry-aligned vocational training. Similarly, the Abia State Health Insurance Scheme improved healthcare access in urban areas, though rural expansion remains critical.

Gov Otti’s policy solutions prioritize localized, context-sensitive interventions. Integrating STEM and vocational training into school curricula—partnering with Aba’s industries—which seems align education with labor market needs. He’s expanding scholarships for rural girls, coupled with community advocacy, to counter early marriage norms. Abia State government’s Healthcare reforms is scaling telehealth initiatives and malaria prevention drives, leveraging local networks like churches and markets for distribution. He’s emphasized that Labor market policies will expand skills certification through the Aba Chamber of Commerce and tech incubators like Umuahia’s Innovation Growth Hub to harness youth talent.

“Institutional accountability is equally vital”, Otti stressed. Participatory budgeting is reducing corruption by involving communities in fund allocation, while public-private partnerships attract investment in school infrastructure, mirroring MTN’s Adopt-a-School program.

Aba’s informal sector offers a blueprint for innovation. The city’s shoe manufacturers, once confined to local markets, now export goods after adopting modern techniques—a transformation fueled by targeted training. Similarly, women’s cooperatives have unlocked microloans for female traders, enabling business expansion.

In conclusion, Otti submitted once that Abia’s human capital challenges demand a dual focus: addressing microeconomic decision-making barriers while strengthening institutions. In my humble opinion, by bridging education with industry, expanding healthcare access, and fostering accountability, the state is leveraging its entrepreneurial culture for inclusive growth. It is true and I assert that success hinges on policies that reflect Abia’s unique socio-economic fabric, transforming human capital from a latent asset into an engine of sustainable development.

Dr Chukwuemeka Ifegwu Eke writes from the University of Abuja Nigeria